Collaborative Change

Changing complex, entrenched social systems to achieve better outcomes for individuals and communities requires patience, commitment, and persistence. It also requires questioning long-standing beliefs about how we tackle common problems, and making room for the insights generated by many diverse points of view.

LEAD enhances public safety and individual health and well-being by better recognizing and remedying the problems experienced by people living with unmet behavioral health needs and/or in extreme poverty.

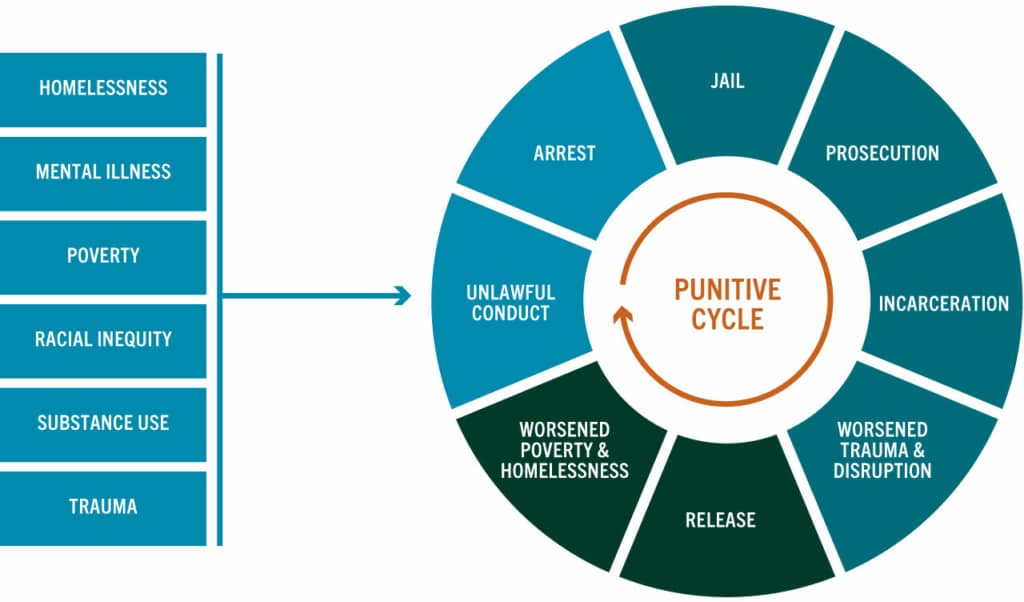

LEAD starts by acknowledging that using prosecution and punishment as a primary response to social disorder has resulted in great harm and little healing. LEAD work does not minimize the pervasive problems often associated with drug use, the drug economy, unaddressed mental illness, and extreme poverty, and accepts that these require robust responses. LEAD is about more, not less – more action, more impact, more support, and more satisfaction – than punitive responses have traditionally generated.

To create alternatives to the criminalization of behavioral health needs and income instability, LEAD reorganizes existing stakeholders into collaborative systems.

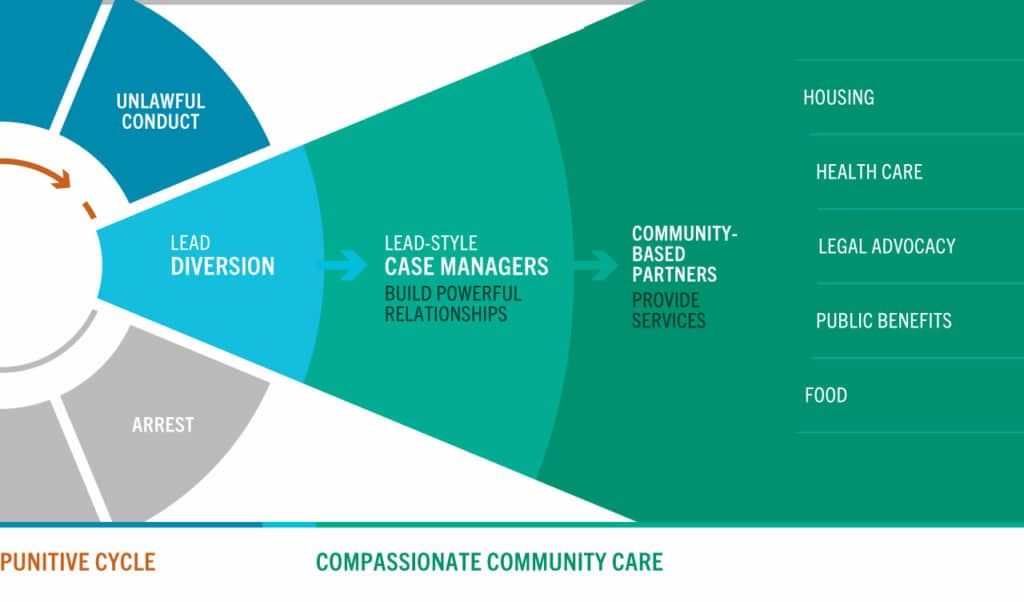

Concretely, LEAD offers a coordinated framework for pre-booking, pre-arrest, or community-based diversion to long-term intensive case managementLEAD-style case management is the heart and soul of LEAD’s effective, coordinated system of care, one that reorients e… More for people who are otherwise subject to criminal legal system response due to unlawful or problematic behaviors connected to drug use, drug activity, mental illness or income instability. The range of offenses and behavior eligible for LEAD referral or diversion varies among jurisdictions and generally expands over time. Participation in LEAD is always voluntary.

Rather than imposing timelines, requirements, mandates, and sanctions, the LEAD model provides individualized intensive case management in community-based settings. By constructing a coordinated, client-focused, long-term, low-barrier system of support and harm reductionHarm reduction is a theory and practice that aims to reduce the level of harm (for oneself and for a larger community) t… More, LEAD provides an effective strategy to address the underlying, persistent factors driving ongoing unlawful or disruptive conduct that stems from complex behavioral conditions.

LEAD’s care approach is voluntary, individualized, and uses evidence-based strategies to support behavior change for people with complex needs and facing high barriers.

There is no time limit for participating in LEAD, and no universal goal or marker of success for all participants. However, every community will want to use its resources efficiently and effectively, which means that case management slots should not be allocated for an extended period to disconnected participants who do not respond to sustained outreach efforts.

Project Management

The project managerThe Project Manager (PM) is responsible for coordinating all aspects of the LEAD initiative and managing its day-to-day … More holds principal responsibility for managing the implementation of any LEAD initiative and for holding the effort true to LEAD core principles. The project management function may be held by a single person in a small LEAD project; however, as a project grows, it will need to be a multi-person project management team.

The project manager is responsible for implementing and supervising LEAD’s day-to-day operations in several realms. But although the project manager serves as the hub of both strategy and operations, it’s important to remember that the project manager is not the “do-er” of all things. The project manager is the chief facilitator, but not the only fixer. Project managersThe Project Manager (PM) is responsible for coordinating all aspects of the LEAD initiative and managing its day-to-day … More report on referrals, intakes, and outcomes, collecting data from case managersLEAD-style case management is the heart and soul of LEAD’s effective, coordinated system of care, one that reorients e… More and, where available, other partners. Project managers also are the primary ambassadors to neighborhood leaders and other community stakeholders, addressing concerns and ideas for improvement, and ensuring that LEAD is felt to be responsive and impactful. They ensure that resources are adequate to support the program scope, and recruit additional resources as needed as the program expands. They facilitate operational and governing bodies and maintain an open channel with partners to ensure the model is meeting the legitimate needs of all.

Referral and Enrollment

There are three ways a person can be referred to LEAD. You can think of these as three doors to the same room:

- Arrest diversionsArrest diversions give law enforcement officers the option of referring people to LEAD at the point of arrest (either pr… More give law enforcementThe term “law enforcement” is used throughout this toolkit to describe police officers, sheriff’s deputies, and others… More officers the option of referring people to LEAD at the point of arrest (either pre- or post-arrest) for diversion-eligible offenses, instead of booking them into jail and referring them for prosecution.

- Social contact referralsSocial contact referrals give law enforcement officers the opportunity to refer people whose law violations may be relat… More give law enforcement officers the opportunity to refer people whose law violations may be related to behavioral health issues or poverty without waiting for a potential arrest.

- Community referralsCommunity referrals provide community partners with the opportunity to refer people who are known to chronically engage … More provide community partners with the opportunity to refer people who are known to chronically engage in problematic, perhaps unlawful, behavior related to behavioral health issues or poverty without police involvement and without using the emergency response system (911 or equivalent).

Individuals referred to LEAD are considered participants once they have completed two steps: (i) they’ve signed a multi-party Release of InformationThe multi-party release of information (ROI) is the essential precondition for ongoing care coordination among LEAD oper… More allowing for care coordination as necessary and (ii) they’ve completed an in-depth psycho-social intake assessment, which becomes the basis of an initial Individual Intervention Plan. Once those steps are completed, the person is considered enrolled in LEAD; if the referral was related to a pre-booking diversion of a specific charge, that charge will not be filed.

Case Management

As the “golden thread” in LEAD, case managers maintain connection with, and support, participants – no matter what – as they navigate various systems, barriers, and obligations.

LEAD case management is relationship-based, founded on trust, and built to endure periodic steps back, self-sabotage, and crises.

Founded on principles of harm reductionHarm reduction is a theory and practice that aims to reduce the level of harm (for oneself and for a larger community) t… More, LEAD case management meets people where they are, physically, mentally and behaviorally – but doesn’t leave them there. LEAD imposes no predetermined objectives or requirements on its participants – instead, LEAD supports participants to achieve as much healing, stabilization, and reduction of harm to themselves and others as possible at any point in their journey. Case managers help participants identify their goals and interests, work to understand fears and impediments, and use motivational interviewingMotivational Interviewing (MI) is a foundational technique for LEAD. An evidence-based approach to supporting positive b… More to support behavioral shifts.

Case managers act as brokers to secure available services, resources, or assistance to advance participants’ progress and well-being. Rather than expecting participants to come to them, case managers must be field-based, as needed. As programs grow, dedicated outreach teams may be used to locate and engage participants in the field, allowing case managers to operate with predictable office and appointment times while still maintaining the flexibility to respond to unscheduled needs and events in the field. Responding to unscheduled calls and reports from law enforcement about participants’ immediate situation and needs is highly valued.

At a minimum, the LEAD care model is low barrier, based in harm reductionHarm reduction is a theory and practice that aims to reduce the level of harm (for oneself and for a larger community) t… More principles, offers intensive long term case management, and brokers other services while providing flexible funds that allow case managers to help meet participants’ needs. Intensive case management and flex funds are a floor, not a ceiling, for the LEAD care model.

The care model can and does evolve as circumstances require and as resources permit. LEAD outcomes will be enhanced if housing and non-congregate shelter, income supports, and access to high quality trauma recoveryRecovery as defined by SAMHSA is “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live … More resources are added to the resource pool available to case managers.

Multi-Agency Case Coordination

Multi-agency case coordination is a fundamental element of the LEAD model. LEAD case managers routinely coordinate with police, prosecutors, judges, other services providers, and neighborhood leaders, as needed, to ensure that a participant’s stabilization plan is well understood and supported. In part, this is to help ensure that no partner inadvertently impedes that plan due to lack of knowledge – for example, by arresting participants on old warrants when they are making great progress and officers have discretion not to arrest.

Criminal cases that either cannot be, or were not, diverted pre-booking or pre-filing are coordinated as well; this coordination may potentially result in partners deciding not to file, not to seek detention, or to dismiss or resolve without incarceration, if the participants’ stabilization would be undermined by the case proceeding on a standard course.

While the LEAD model is centered on pre-booking referral (or even earlier in the GAINS Sequential Intercept ModelThe Sequential Intercept Model was developed as a conceptual model to inform community-based responses to the involvemen… More, via community referrals or pre-arrest referrals from law enforcement), other criminal legal system agencies (courts and prosecutors) may also initiate referrals in a pretrial or post-disposition posture.

It is essential, however, that post-filing referrals not dominate case management slots, lest a perverse incentive be created to send people further into the criminal system in order to get assistance that should have been available at an earlier stage. Pre-booking diversions from law enforcement, and, secondarily, community referrals that bypass the call-for-service system entirely, must always have at least equal access to case management slots.